Engineering and Mining Journal - Whether the market is copper, gold, nickel, iron ore, lead/zinc, PGM, diamonds or other commodities, E&MJ takes the lead in projecting trends, following development and reporting on the most efficient operating pr

Issue link: https://emj.epubxp.com/i/938385

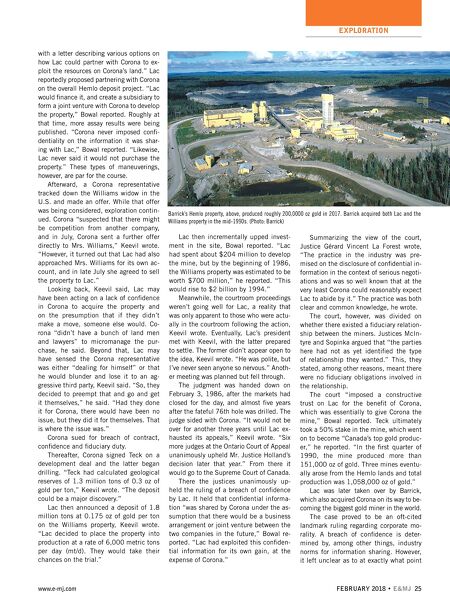

EXPLORATION 24 E&MJ; • FEBRUARY 2018 www.e-mj.com The idea, Teck Resources Chair Dr. Nor- man B. Keevil said, was to write a history of the family business and to summarize roughly a century of Canadian mining his- tory. The resulting 460-page book, Nev- er Rest on Your Ores: Building a Mining Company, One Stone at a Time, released last year, homes in on a number of topics and provides several lessons on goal-gen- eration and macro strategy, long-term decision-making, and strategic consoli- dation in a sometimes-tumultuous sector. One that speaks to exploration crews and geologists is the topic of avoiding lit- igation that can arise from coordinating prospecting efforts with other companies, hunting so-called elephants, and trying to lock in contracts. Keevil's book spends a few dozen pages covering a couple of law- suits spawned from exploration and devel- opment contract negotiations turned sour. In them, the courts are forced to decode industry norms and officiate seemingly informal negotiations that are typical for the sector. "These things come up all the time," Keevil said. "In the business, you get people doing high-risk deals and you don't have an army of lawyers," he said. "And you shouldn't have an army of law- yers on every high-risk deal because you'd be paying the lawyers more than you pay for drill holes." This means that in many cases, a ge- ologist has to double as an amateur law- yer, he said. "It is not easy because none of us are trained to do that," Keevil said. "So, two exploration geologists decide on a deal and 999 times out of 1,000 there is no discovery," he said. "But when there is one you look back and say, 'holy smoke, why didn't I do this right?'" In one such major case, it took years of litigation before the Supreme Court of Canada sorted it out. Corona v. Lac Gold was first struck near Hemlo, Ontario, in 1929. Claims were staked after World War II. One of the claimants, "a Dr. Wil- liams," secured a title for a property and "did some exploratory drilling in 1947," Keevil wrote. Among other prospectors plying the area, Teck Hughes did some drilling near the Williams property in 1951, finding "nothing interesting" at the low gold price of the day. Decades later, International Corona Resources Ltd., a publicly listed junior mining company, staked a claim and got permission to do some explorato- ry drilling in the same area. "The early, near-surface results were similar, narrow, and not particularly high grade in gold," Keevil wrote. By the spring of 1981, Corona had drilled 75 holes at a cost of roughly $2.5 million. "Corona had only found narrow zones that didn't appear to be econom- ic to mine," Keevil wrote. The 76 th , and deepest, drill hole by geologist David Bell "hit pay dirt." The economic ore apparent- ly ran beneath the surface mineralization. Corona published some of the results as news releases and in newsletters, which got the attention of Lac Minerals Ltd. The latter visited the property on May 6, 1981. There, Lac viewed confidential docu- ments, to include maps, assay results and drill plans, and was advised of the esti- mated potential of the deposit. Bell shared his theory that that the deposit was stra- ta-bound. "He thought it might be volca- nogenic, genetically related to the original volcanic activity that laid down the rocks in which it occurred," Keevil wrote. And the favorable rocks apparently extended west, under the Williams' property. Corona told Lac it intended to acquire the Williams' property, and Lac responded that "this would be a good idea," Keevil wrote. Other sources word it slightly differ- ently. The Canadian supreme court re- ported, "Corona was advised by Lac to aggressively pursue the Williams prop - erty." Separately, University of Calgary professor, Peter Bowal, in a review of the case for Law Now, reported, "Lac advised Corona to pursue the Williams property." Lac proposed a joint exploration agree- ment. Corona wasn't ready for a deal, Keevil wrote. "They were having too much fun exploring, but each side agreed to keep in touch." Bowal reported, "No confidentiality measures were discussed at this meeting." Similarly, the Supreme Court reported, "The matter of confidenti - ality was not raised." After the meeting, Lac acquired gov- ernment maps and land ownership data, Bowal reported. "Lac geologists deter- mined that about 600 claims should be staked in the area and immediately began staking claims." A couple of days later, the companies met at Lac's headquarters, reported Bow- al. "The geology of the area was further discussed along with potential high-level terms of an agreement between the two companies," he reported. "Lac followed up Prospectors and Developers Beware After reviewing a century of Canadian mining in his new book, Teck Chair Norman Keevil tells E&MJ; two lawsuits shed light on the legal implications of seemingly mundane exploration contract negotiations By Jesse Morton, Technical Writer Dr. Norman Keevil's 2017 book tracks the rise of Teck Resources and summarizes a century of mining in Canada. (Image: McGill-Queen's University Press)