Engineering and Mining Journal - Whether the market is copper, gold, nickel, iron ore, lead/zinc, PGM, diamonds or other commodities, E&MJ takes the lead in projecting trends, following development and reporting on the most efficient operating pr

Issue link: https://emj.epubxp.com/i/938385

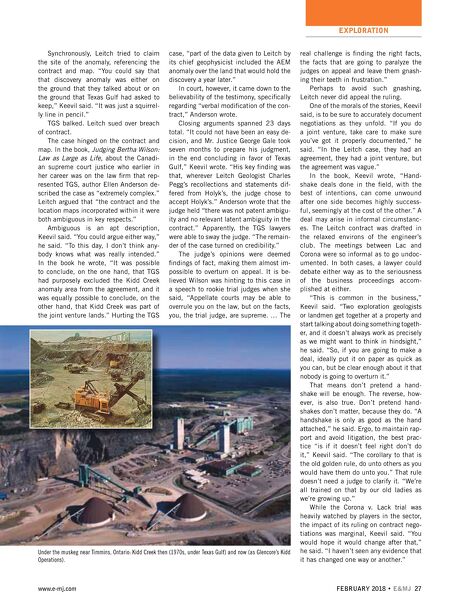

EXPLORATION FEBRUARY 2018 • E&MJ; 27 www.e-mj.com Synchronously, Leitch tried to claim the site of the anomaly, referencing the contract and map. "You could say that that discovery anomaly was either on the ground that they talked about or on the ground that Texas Gulf had asked to keep," Keevil said. "It was just a squirrel- ly line in pencil." TGS balked. Leitch sued over breach of contract. The case hinged on the contract and map. In the book, Judging Bertha Wilson: Law as Large as Life, about the Canadi- an supreme court justice who earlier in her career was on the law fi rm that rep- resented TGS, author Ellen Anderson de- scribed the case as "extremely complex." Leitch argued that "the contract and the location maps incorporated within it were both ambiguous in key respects." Ambiguous is an apt description, Keevil said. "You could argue either way," he said. "To this day, I don't think any- body knows what was really intended." In the book he wrote, "It was possible to conclude, on the one hand, that TGS had purposely excluded the Kidd Creek anomaly area from the agreement, and it was equally possible to conclude, on the other hand, that Kidd Creek was part of the joint venture lands." Hurting the TGS case, "part of the data given to Leitch by its chief geophysicist included the AEM anomaly over the land that would hold the discovery a year later." In court, however, it came down to the believability of the testimony, specifi cally regarding "verbal modifi cation of the con- tract," Anderson wrote. Closing arguments spanned 23 days total. "It could not have been an easy de- cision, and Mr. Justice George Gale took seven months to prepare his judgment, in the end concluding in favor of Texas Gulf," Keevil wrote. "His key fi nding was that, wherever Leitch Geologist Charles Pegg's recollections and statements dif- fered from Holyk's, the judge chose to accept Holyk's." Anderson wrote that the judge held "there was not patent ambigu- ity and no relevant latent ambiguity in the contract." Apparently, the TGS lawyers were able to sway the judge. "The remain- der of the case turned on credibility." The judge's opinions were deemed fi ndings of fact, making them almost im- possible to overturn on appeal. It is be- lieved Wilson was hinting to this case in a speech to rookie trial judges when she said, "Appellate courts may be able to overrule you on the law, but on the facts, you, the trial judge, are supreme. … The real challenge is fi nding the right facts, the facts that are going to paralyze the judges on appeal and leave them gnash- ing their teeth in frustration." Perhaps to avoid such gnashing, Leitch never did appeal the ruling. One of the morals of the stories, Keevil said, is to be sure to accurately document negotiations as they unfold. "If you do a joint venture, take care to make sure you've got it properly documented," he said. "In the Leitch case, they had an agreement, they had a joint venture, but the agreement was vague." In the book, Keevil wrote, "Hand- shake deals done in the fi eld, with the best of intentions, can come unwound after one side becomes highly success- ful, seemingly at the cost of the other." A deal may arise in informal circumstanc- es. The Leitch contract was drafted in the relaxed environs of the engineer's club. The meetings between Lac and Corona were so informal as to go undoc- umented. In both cases, a lawyer could debate either way as to the seriousness of the business proceedings accom- plished at either. "This is common in the business," Keevil said. "Two exploration geologists or landmen get together at a property and start talking about doing something togeth- er, and it doesn't always work as precisely as we might want to think in hindsight," he said. "So, if you are going to make a deal, ideally put it on paper as quick as you can, but be clear enough about it that nobody is going to overturn it." That means don't pretend a hand- shake will be enough. The reverse, how- ever, is also true. Don't pretend hand- shakes don't matter, because they do. "A handshake is only as good as the hand attached," he said. Ergo, to maintain rap- port and avoid litigation, the best prac- tice "is if it doesn't feel right don't do it," Keevil said. "The corollary to that is the old golden rule, do unto others as you would have them do unto you." That rule doesn't need a judge to clarify it. "We're all trained on that by our old ladies as we're growing up." While the Corona v. Lack trial was heavily watched by players in the sector, the impact of its ruling on contract nego- tiations was marginal, Keevil said. "You would hope it would change after that," he said. "I haven't seen any evidence that it has changed one way or another." Under the muskeg near Timmins, Ontario: Kidd Creek then (1970s, under Texas Gulf) and now (as Glencore's Kidd Operations).